why art cannot be taught James Elkins

Note to readers who find this online:

This This conversation was held at Cork Caucus, Cork, Ireland, 2005, and published in Cork

Caucus: On Art, Possibility, and Democracy ([Cork]: National Sculpture Factory and

Revolver, 2006), 247–59. This is a partly edited version; the definitive version is in Cork

Caucus. !

The book that’s mentioned here is Why Art Cannot be Taught. Several sections of it are free

online on the site https://saic.academia.edu/JElkins/Papers.

!!

Why art cannot be taught – James Elkins

!!

Editor: Never one to shirk from discussing the most controversial topics, at times

bordering on the politically incorrect, (and) yet with an undeniable capacity for

generating serious conversation, here – trying to burst one of the principal bubbles of

the Caucus itself – the widely published author and Professor, James Elkins,

broaches the prickly subjects of why art can’t be taught, nor reduced to merely talk.

In conversation with several local artists and international participants, he supports

his argument by reference to literary criticism, through recourse to the Kantian

origins of critique, and finally by focusing his claim on the difficulties encountered in

the so-called crit (critique) session. That the conversation deteriorates to a minor

pitched battle – in the garden of the Convent which housed the Caucus Centre – for

art being “very, very rational” on the one hand and “ninety-nine percent irrational” on

the other, we find productive for making plain once again, the caesura parameters of

the middle section of the book.

!!

James Elkins: When Tara asked me to do something I thought a reasonable thing to

do that doesn’t get discussed much in the art world is basically talk about how hard it

is to talk about art. And by that I mean the strangeness of the art work, the fact that

it’s visual, the fact that it tends to be something that doesn’t fit very easily with ways

that people talk. So I had this notion that we would talk about two things in particular

that make art really, really hard to address: one of them is; why art can’t be taught

and the other subject is how hard it is to talk about art in critique settings, or

critiques. About half of the book I wrote called Why Art Can’t Be Taught actually ends

up being about critiques, because critiques are, I think, one thing that sets what we

do apart from stuff that gets done in most other, if not all other, fields that would be

taught in colleges and universities. I know some people sort of deny that; they would

say that art is something that you can talk about in the way that you talk about

physics or chemistry, that you get better at it and so on. The fact is that no other field

in universities or colleges, has critiques for its examination system. If you are a

physics student, you don’t get freewheeling conversation at the end of the teaching

period, with your adviser and then they decide, OK, you’re ready for the next year.

You get questions, serious questions. But for some reason, it doesn’t work that way

in art.

!

One of the things to conclude from that is that art doesn’t have a step-wise set of

things you can learn to go from one stage to another. Nobody can agree what that

might be in art. It can’t go that way, it has to go through these conversations that end

up being called critiques. The second subject would concern how conversations

about art are irrational. And my own take on this is that an art school critique, or a

serious kind of conversation about art, is just about the most irrational thing you can

do and still be speaking right. I think they are about ninety-nine percent irrational, but

it is possible to figure out some things about them and to try to keep a bit of control

over them and that’s what I end up writing about in the book. The question is a

practical one, for how in the world do you make sense out of what’s happened when

you’ve had a critique.

!

I have a little list of reasons why I think critiques don’t make sense: a list of eleven.

These would be things to fight against. So, in my classes I wouldn’t say to anybody ‘I

like that, that’s good, that’s bad’, but the conversation is about the conversation. How

do you talk about art, how have people talked about your art in the past, what kind of

things have they said, have they made any sense, could they have made more

sense, would there be a way to make some sense out of them? In my class in

Chicago what we do – and I’ve taped a bunch of critiques and typed out the

transcripts – is to slow them way down by reading them. Of all the different

suggestions that I have to improve art conversations, that’s the best one I think.

The first one of eleven is that nobody knows what an art critique is, as opposed to

other kinds of critiques. The thing to know about the history of critiques is that the

word comes out of the Kantian critique, and what Immanuel Kant meant by a critique

was completely different from what anybody these days means by critique. A critique

in his way of thinking was ‘an inquiry which tells you the limits of your thinking’. It’s

not to judge, it’s to find how far you can think, where you have to stop. This kind of

critique is in the background of what we call critiques, but obviously something

fundamental has changed because, in what we call critiques, the point is to judge. If

you do a pure Kantian critique you don’t judge.

!

In the eighties there was a movement in the art world to try to turn critiques into the

old fashioned critique. An art critic’s job was supposedly not to judge anything but

only to understand the conditions of their judgment, to understand what is was that

led them to make judgments. That was a movement in post-structuralism and of

course it doesn’t work, because you can’t encounter an art work and say nothing

about it except why it is you feel you might want to judge it. That’s too much navel

gazing. So if critiques have something to do with judgment and not just the Kantian

sense of figuring out the limitations on your own thinking, then the question is ‘well,

what are the terms of judgment’ – so you have then a wide-open field of possibilities.

!

Take an example at hand. In the convent, presumably you would have religious or

ethical judgments that you would be after. In some philosophic settings you would

have critiques where the point would be moral judgments. You could have critiques

in education settings where the point is pedagogic judgments. The problem with art

world critiques is that nobody knows what the terms of judgement are. I think there

might be some agreement that we don’t want to just say that the work is good or bad

although that would be a perfectly legitimate kind of judgment. And there might be

some agreement that we don’t want to say that the work is beautiful or not, but that’s

a classical Kantian aesthetic judgment so that’s a legitimate kind of thing but the art

world doesn’t do much of that either. At least in Chicago my students are totally

allergic to beauty; they don’t want to be told their work is beautiful, its like being told

its kitsch, its bad or its useless. So then, if we’re also going to have no aesthetic

criteria, no judgment of beauty, we’re left with a really strange bunch of terms for our

judgments and the most interesting one is the word “interesting.”

!

When somebody says to you that your work is really interesting, as far as I’m

concerned anyway, this means nothing. It‘s like a placeholder; I will say add to this in

a moment. That’s a kind of art world evasiveness, it’s not really quite a judgment yet,

it’s like a pseudo-judgment. And you could make a little list of these: powerful, that’s

always a good thing to say. Who doesn’t want their work to be powerful, but then

again, exactly what does that mean? Authentic, your work is authentic, which means

what? It’s a good thing you’re not a sham! Moving, your work is moving, but what

does it say, why is it moving, what is it moving about? Inventive and original are sort

of avant-garde criteria. Difficult, that’s another avant-garde one, But then as with the

others, the content of the judgment is missing. In my mind they’re all connected with

the fundamental one of interesting, because they are all more or less content free.

You would have to then go on and ask what made them that way, and interesting is

good for social reasons because if someone says your work is interesting, one thing

that they might mean is that they don’t want to turn around immediately and run

away. They are willing to stay there and look at it a little while, so interesting also

means something might happen later, that the work will keep them there somehow.

!

Maud Cotter: I think it’s interesting when it prompts you to see things differently in it,

when it opens other perceptual possibilities…if I use that word about somebody’s

work it’s because it makes me see the world in a different way.

!

James: If a person says it is honest, it can be totally dishonest if you hate the work

and because you can’t say that, you say ‘oh that’s interesting’. It can also be

passively dishonest if you can’t think of anything else to say but the honest

interesting, I think it is like that, it means that something’s happened which you don’t

know how to put into words yet.

!

Maud: It is a hovering kind of a word too. It allows you to suspend judgment.

(Maud took out rest of this piece)

!

Tara: It’s a waiting stage, a willingness to engage.

!

James: Or, to defer judgment.

!

Maud: Sometimes if you see something that has had an effect on you, it has to go

down and come back up the next day. Its maybe only a day or two later you get

another signal.

!

Tom Curtin: Maybe you’re just waiting to see what everyone else has to say first.

!

James: A question of holding back. I think in a social situation, with friends and

visiting a studio, I think interesting would probably be honest. In a school situation, in

my experience, interesting is usually dishonest, because one of the things that art

students don’t always realise, is that if you have an instructor who’s over the age of

thirty/thirty five, they’ve probably seen work like yours a lot before. If you have an

instructor that’s pushing up towards sixty they’ve certainly seen what you’re doing

before, and so one of the challenges for art instructors is to try to be enthusiastic,

engaged, polite and all the rest of that, and ‘interesting’ is really handy for that .

!

Jan Verwoert: I hate to sound like a critic here, but I think that ‘interesting’ comes into

art critical discourse at a very precise point in the history of aesthetic discourse, the

beginning of the nineteenth century, and the terms ‘interesting’ versus ‘boring’ mark a

very significant transition from an older vocabulary of what was ‘beautiful’ and not

‘ugly,’ which was the Classical aesthetic where art is believed to be a manifestation

of natural beauty. It appears first with Friedrich Schlegel. It’s a shift in aesthetics from

the Classical to the Modern, where the new paradigm is exactly what you have said:

that art is no longer primarily judged in terms of whether it articulates natural beauty

but whether it touches us. To speak about the interesting and the boring in a sense

confirms that you have entered the modern age. I don’t find anything phony about it.

It is the primary judgment operative in modernity and there is nothing wrong about

being modern.

!

James: I agree with you half way. I think the history is exactly right and the whole

history of what counts as boring is also a very interesting thing. I would just be a little

bit careful about saying that it’s not phony, because there are so many terms of

judgment, not just the aesthetic turn to the Romantic, not just the turn to Modernism

as you say, but there are so many other terms, the ethical, pedagogical and all the

rest of these terms and they get mixed up in art critiques so much that it can be

messier than you suggest. You see, I’m not disagreeing with you, but it seems to me

that it doesn’t solve the problems that actually come up in art conversation. There

can be all kinds of reasons why someone uses this word and its many synonyms

and false friends, as they say. I think there is a kind of flora and fauna of judgment,

but you’re absolutely right that, if you trace it historically, you do have that moment in

which that turn takes place and I think you could find at least one or two others. You

could talk about a turn in the Renaissance from a theological truth to a secular truth

– something Derrida does.

!

Jan: I would just say that, in very pragmatic terms, these words are a port of entry

into the discourse of modern art. It’s the tools we have and they haven’t been

replaced yet so we can’t help using them. After that, you have to give reasons, and

people can check whether you are talking bullshit or not. It’s just a way to open up a

discourse, it’s a gesture, and afterwards, what you say has to be verified in relation

to the object and then everything becomes very rational because everyone will be

able to see whether you talk nonsense or not. Whether what you are saying makes

sense in relation to the object.

!

James: Now you are beginning to sound like a high-modernist.

!

Sarah Iremonger: Yes, does that not open the possibility of intellectual snobbery?

!

Jan: No, everybody can check. It’s very democratic, everybody with an aversion to

bullshit will be in a position to judge what you say.

!

Maud: But doesn’t a language bend and evolve to suit everybody’s individual

aesthetic? I think in some ways, being an artist and finding a way of talking about

your work is about forging a language around your work, making it an individual

space. But while there is the personal aesthetic, there is the grammatical almost

structured way that you are talking. I am beginning to believe less and less in things

that exist as they are, and more and more in the complete relativity of everything. I

can’t say that I’d be thrilled to systematise my thinking in any way. I think the only

way of finding a way forward is to somehow evolve a personal language and then

maybe get that challenged.

!

James: One of the things that happened in the last twenty years or so in criticism is

the appearance of locutions of the sort; ‘my work addresses this, my work opens this

question, my work interrogates, my work explores, my work unpacks’ (one of my

favourites), or ‘I can’t unpack this now’ (the academic version). If you look at these

things when they come up in art writing, usually nothing follows. It doesn’t say what it

is that is actually being explored. You say ‘my work explores gender relations’ but

what was the content of that exploration? So again, without saying that I disagree

with this, it’s the forms of it that matters and there’s something new about that

particular coyness that wasn’t there before, although it’s in the same historical fold

for sure.

!

Since you brought up this genealogy, (would read better as – ‘since this genealogy

has been brought up,) I have a little list here of four different kinds of critical

orientations from the literary critic, M.H. Abrams. In the forties he wrote a book called

The Mirror and the Lamp, which is still a fundamental book on literary theory and

literary criticism. The first of four different orientations of criticism is mimetic, and for

him that means that you judge an artist’s work according to how well it matches

nature. The second one is pragmatic criticism, criticism intended to help the artist

please, delight, move or instruct. Pragmatic instruction would be a way of helping

people to get their work in the world, have it speak more effectively.

!

The third is what he calls expressive. That is criticism intended to help the person to

make the work be more expressive. That is a romantic idea. The last critical

orientation is what he calls objective criticism. That is when the person who’s doing

the talking is trying to talk only about the work. In the art world this is usually called

formal criticism, although that would be technically a little bit different. Objective

criticism is when you pretend for the purposes of conversation that there’s nothing

outside the art – that the art is all you’re talking about, its form and structure, its

composition. Abrams says that these four, the mimetic, the pragmatic, the expressive

and the objective, constitute the field of criticism. I think the last one of those is a

fiction; there’s no way to talk just about an artwork without bleeding into these other

kinds of critique. That can be helpful, because what tends to happen is that people

quickly veer from one to another in ordinary conversation so fast and in such a

confused way that the task becomes whether you can tease them apart.

!

The second reason why critiques are difficult is they are often too short. I think it

would be reasonable to say that when you step into someone’s studio for the first

time and you see the work, unless you know what to expect, it’s going to take you at

least five to ten minutes just to get your bearings, and then at least another twenty

minutes to ask pertinent questions and you’re probably not going to run out of

questions for half an hour or an hour, at the minimum. So for me, ten or fifteen

minutes is not enough to do anything except to start to formulate the questions that

you want to ask about the thing.

!

Tara: Are you aware of Static’s project as part of Cork Caucus? It’s called

EXITCORK and is devised by architect and artist Paul Sullivan and Becky Shaw. It

will basically result in every fine art graduating student in Cork’s Crawford College of

Art, getting two reviews of their final year show from critics, writers and arts

administrators in Cork. They want to expose how criticism is dished out, who gets

reviewed and why and make transparent the views of the movers and shakers within

Cork and the international art world, which are often not transparent. But they also

want to make transparent the difficult position those making judgments are put in as

they open themselves us to judgment by the reviewed!

!

James: I think these problems are hard in school and they’re hard in this kind of

setting but I think the place where they’re really the toughest is when you’re out there

in the world as an established artist and you have a bunch of friends who like you.

That can be the most dangerous thing of all, because then you just get a lot of pats

on the shoulder. That can be seriously dangerous, asphyxiating even.

!

Maud: I got out of the country because I felt that everything was much too

confirming. might this word be confining?

!

Sheila Fleming: The development of that now is the amount of open submission

shows around the country even compared to ten years ago. I think we are in a

developmental stage here, there are so many opportunities; perhaps the writing and

the critical environment will come after.

!

James: Perhaps, but the art world is also full of really overly short notices and overly

polite social gatherings. The politeness phenomenon extends to newspapers too. In

a country this size no one wants to write something nasty and wake up the next

morning and be in the same place.

!

Anyway, number three is a distinction between people who report thoughts after

they’ve thought them up and people who discover their thoughts while they’re

talking. This latter is a really common type. Art is confusing so its excusable, but

there are a lot of people out there who have an invisible microphone in front of them

and will just talk and talk and talk. The problem being they are discovering what they

think while they’re talking, which is desperately confusing from a student’s point of

view. It’s much better from the artist’s point of view if you get your friend or your

teacher to just be quiet for ten minutes and only then say something, in order to

minimise the chances that they’re discovering their own thoughts while they’re

speaking. That’s a basic thing about any kind of human interaction, but I think with

art it’s exacerbated because new art is meant to be a bit confusing so it can make

talk about it doubly confusing.

!

The fourth reason critiques can be difficult is that teachers make their own art works

which are different from yours, which means, when it comes right down to it, that the

teacher doesn’t like your art work because if they did they would have made it. So

there is a negative judgment right there to begin with, and this of course goes for

anybody who sees anybody else’s work who is themselves an artist. Would read

better as who are themselves artists

!

Rory Mullins: One of the things that came up in the Static workshop was people

realising that we all had one student to review and some people went into the room

and immediately went ‘I hate this, I can’t review it.’ They realised they were incapable

of even seeing what was there, so not even getting to the stage of critiquing it.

!

Maud: I did teacher training, and you do educational psychology, psychology of

attention and retention and all that business, and you’re supposedly taught how not

to be prejudiced. When you’re teaching children you have got to be alert to their

individual minds. They are all so incredibly different. If you don’t make a leap into

their unknown you can damage them, because you pre-determine and pre-judge

where they’re going to go, developmentally. It’s a little bit like that with art.

!

James: There’s a brilliant essay called Boutique Multiculturalism (Ed: it’s an essay,

and essays are usually not italicized; they’re usually in quotation marks. Even if this

is house style, please change it — thanks.) by the literary theorist Stanley Fish. His

claim is that none of us is a multi-culturalist, that in other words, none of us is really a

pluralist who’s willing to like everything else. The example he gives is the fatwa

against Salman Rushdie. He says imagine you’re an Islamist who’s spent their entire

life studying Islamic culture and you’re really deeply sympathetic with it and then you

read about the fatwa, well, you’re not gonna pick up a gun and go out and try to find

Salman Rushdie. Why not? Because you’ve drawn a line there somewhere, and

what Fish says is that everybody has a line like that, and therefore no one is what he

calls a strong multi-culturalist; everybody is a boutique multi-culturalist just picking

and choosing a nice little bouquet for yourself which counts for you as your

tolerance. It’s a very provocative, cynical thesis but the parallel in the art world is a

good one.

!

The fifth reason is that teachers make very idiosyncratic pronouncements. And here I

would also take a bit of theory from Stanley Fish. Fish is famous in literary criticism

because he invented what’s called ‘reader response criticism’. He wrote a book

arguing that there is no text in the class. Reader response criticism means that a text

has no intrinsic properties but it is what people bring to it. In Fish’s way of thinking,

every artwork has value because there is what he calls an interpretive community, a

group of people who’ve more or less agreed on what its values are. But those

interpretive communities can shift and change and nothing intrinsically belonging to

the artwork can ever control what people say about it. Generations can come and go

and people can say anything about anything that they want. Even when artwork

seems to be eternal, take Rembrandt, Rembrandt only has the qualities he seems to

because the interpretive community is so enormous. It consists of two billion people

over three centuries who love Rembrandt for the same kinds of reasons. But when

you come to contemporary art, interpretive communities are really small – and this is

something that may come up in Gayatri Spivak’s lecture too, dimensions of

democracy hinge on this – the art-world is of course small and within it you have

people doing problematic practices that are not understood by the whole art world.

And they are not only small but also evanescent; people change, a group can

change its judgment about a work very quickly, month-to-month, minute-to-minute.

So reason number five that art critiques are hard to understand is because you can’t

tell, unless the person is wearing a badge, what interpretive community they

represent; are they just representing their one psychotic self or are they representing

an interpretive community that have followed geometric abstraction since the

twenties, or something more stable still?

!

Jan: You can check. You read art criticism; you are a clever person. You should be

able to understand where they are coming from. You are playing the role of the naive

cynic and you’re not. If you are interested you can find out.

!

James: The kind of thing that I would be claiming here is that in the world of

contemporary art you are in a place which is particularly treacherous in terms of

interpretive communities. If you go to the Louvre and you stand in that crowd of

people that are looking at the Mona Lisa, you’re pretty safe in interpreting the oohs

and aahs. The kind of thing that I would be arguing is that this is particularly

treacherous in contemporary art where things shift and change very quickly and

groups are often very small and hard to check. So I’m saying, it’s relative. I’m not

claiming the social contract is negated.

!

Daniel Jewesbury: From what I remember of reading Fish, he maintains that any

principled position is ultimately bogus and that it is a kind of self-delusion anyway.

Are you going along with that? Your use of the word ‘idiosyncratic’ suggests that

anybody who speaks from a certain position is, by virtue of that position, bogus or

suspect.

!

James: I wasn’t trying to say that exactly, and I wasn’t using that part of Fish’s

interest. I was thinking more of sources of consensus among people hence the Mona

Lisa effect. I also feel funny about saying that anything is bogus, because you can be

a really interesting interpretive community of one, your principles can be quite ironclad

as it were. Its more a matter of how the social contract is operating when you’re

in a group that is shifting and changing.

!

Sheila Fleming: I have to say that as a student, reading anything published or

someone else’s writing gives you the opportunity to check your own eye and

knowledge. Sometimes even an Aidan Dunne (art reviewer for the Irish Times) article

helps, even though it might not be as fulsome, and he has to write for a certain public

and in a certain kind of way.

!

James: One of the biggest disagreements we had at the Ballyvaughan “States of Art

Criticism” roundtable — that is, the even that will be the core of the book of that

name, which is vol. 5 in the series The Art Seminar, which I am editing at UCC —

does this need a note to explain what it was? was between people like me who

wanted to think of all kinds of newspaper art criticism along with ‘academic criticism,’

and people on the other hand who did not want to include the Aidan Dunnes of the

world, because it isn’t serious art criticism. Some people just want to say that that is

different from what they would count as serious criticism, but perhaps its more a

matter of having a text there that you can think about, it’s relative. This was a

disagreement that we didn’t resolve.

!

The sixth reason is that critiques are very emotional. The critique is not a situation

where you can be detached, because the artist, of course, is very close to their work.

It struck me a couple of years ago that one of the ways you could think about a

critique is that it’s like a seduction. The student is trying to get their artwork to be

seductive, but you also don’t really want that to happen because what you want to do

is get a certain amount of feedback. You want to learn something. It is always nice to

sell a work, but what you’re really looking for then is an arc of immediate enthusiastic

acceptance followed by an amicable separation.

!

The seventh reason critiques can be difficult is that they are like a number of other

conversations with which they can be conflated or confused. For example, a critique

can be like an exercise in translation, because you’re trying to translate something

visual into something that is verbal. You’re trying to translate the critique from the

way you talk into the way the person is talking, so it can be like a conversation

between two people who are not fluent in the different languages each other (are) is

speaking. There have been some things written about critiques as story-telling. The

problem with that is that at some point you usually want there to be some truth in that

the critique is not just a story-telling time, it’s also a situation in which you want to be

getting across something which is true.

!

I think my favourite of these is that critiques are often a lot like legal proceedings,

because you set out the evidence that your work is really good, that its ‘not guilty’; if

you have someone who’s not convinced by that you have to argue your case. The

difference, of course, is that the artwork doesn’t get freed or executed at the end of

the critique, its more like the way legal proceedings take place in Kafka – they just go

on and on and on and there’s endless evidence and there’s endless ways to argue.

!

Jan: What I am trying to say is that when I work as an art critic, the situation I find

myself in is mediating between a subjective case or a totally subjective story and the

relative objectivity of the public. That is exactly how Kant describes aesthetic

judgment, in his Critique of Judgement. On the one hand, every artist has some

subjective story to tell and, on the other, an objective audience or press; some kind

of language in which to make themselves understood, and in that language you can

always trace the more or less objective steps that someone is taking toward that

end. In that language you are always mediating between the subjective which is the

story the objectivity that comes through the story and which is told, and the audience

that is addressed. So the problem that I have is that I see all the problems you are

describing but I see them as a task and as a challenge.

!

James: I’m not sure if I would disagree with that. The point I make in the book is that

art critiques are actually absolutely wonderful because they’re ninety-nine percent

irrational.

!

Jan: It’s not ninety-nine percent irrational. It’s very, very rational.

James: Well there we might disagree.

!

Jan: I would say it’s just different from official rationality, that it is a constructive form

of rationality. In every artwork you go from A to B to C, and maybe in a very

idiosyncratic way, but if you do analysis of that kind, you can perhaps understand

why someone has taken certain steps. You can describe that, and, of course, in

describing, someone else can judge whether your description makes sense or not.

James: I think you are an interesting person because you are very idealistic and

optimistic.

!

Jan: No. I am totally pragmatic.

!

James: But your pragmatism is very optimistic because the art world would often be

considered a place where these kinds of encounters, adjudications, comparisons or

references to interpretive communities never take place. A lot of people would say,

you may have a review in frieze and another one in Parkett, but where is the person

who is gathering them together to see how they fit into any coherent set of claims? A

lot of people would say that the art world doesn’t have those people.

!

Jan: Every reader can check.

!

James: They can, but it doesn’t happen in print. A lot of people would say that the art

world speaks in many, many voices and defers this moment.

I think this is part of an interesting but different conversation. I don’t know many

critics who, for example, take newspaper art criticism seriously. The historians who

do this kind of work don’t usually bother with newspaper art criticism. These acts of

adjudication don’t take place. frieze does not get quoted in footnotes by art

historians. That’s the thing. There isn’t this moment. So I am more cynical. And I am

happy with the state in criticism where these conversations are separated, but it

means I cannot appeal to the notion that there are these moments where people can

check to see how this discourse fits with this discourse.

!

Jan: I strongly believe that. For me it is a necessary fiction to maintain some

intellectual responsibility. It is not idealist. I think it is politically pragmatic. The

biggest contradiction that you face as an art critic is that your work is illegitimate, but

also that it is standing fast, calling out to be answered and criticised. That’s what’s so

exciting. On the one hand you feel it is necessary to write this but on the other hand

you feel you have to prove it. There is always the risk that you might write complete

nonsense. You can never answer that, you have to keep on writing, but there are

readers who can test that.

!

James: I wouldn’t disagree with anything up to the last phrase. Anyway, number

eight is that teachers waste a lot of time usually giving technical advice. In my

experience more conservative art schools would be almost all technical advice about

glazes or whatever it is in your medium. On the other hand, in art academies and art

institutions with an international presence, especially at the higher levels, there can

be a reticence on the part of instructors to give any technical advice. The assumption

being that once you get to a certain point as an artist whatever technical faults you

might have are no longer to be understood as faults. Both sides of the spectrum lead

to problems, and it’s inherently a difficult subject because there isn’t a plausible

discourse that can link the technical with the other than technical.

!

Number nine is that some teachers are adjudicative and others descriptive. Most

teachers are adjudicative, which means they are out there to judge. Other teachers,

who are rare but really interesting, are descriptive; their purpose in life is to describe

the work as eloquently as they can, and ask you questions without incorporating

explicit judgments. Usually these two don’t mingle very much.

!

The tenth is that your presence, as the artist, can be confusing to the people who are

writing and speaking and in art schools it’s a common assignment that when you get

a critique you’re meant to say something first. I think that a good way to think about

this problem is as something that goes back to German Romanticism: the idea that

the point of an Art Academy in the end is to find the student’s expressive potential as

an individual.

!

The eleventh and last point that makes critiques difficult is that artworks are

unoriginal. The problem here is that that a lot of the rhetoric of the art world is geared

up to praise things that are original. It’s very hard to find words to praise ‘average

art’.

!

Rory: How many of the flaws would be substantive of the whole process or

endeavour of critiquing?

!

James: Some of these are pretty inherent. Maybe the first one, the kinds of

judgments that people say are inherent.

!

Jan: One thing I don’t completely understand are the implications of what you are

saying, what do you want, why are you stating what you are saying?

!

James: Reviewers of my book said that I should be claiming there are actual fixes,

ways to fix critique and turn it into something else. In other words, some of these

things that turn around and seem to be positive recommendations read as if I was

trying to diagnose a problem; that this is what we should be doing. But I didn’t do any

of that, because as far as I am concerned my interest is simply that these things are

so challenging. They are far more interesting, as it were, than a conversation in a

science lab about fixing a piece of equipment, or indeed any kind of conversation

that is systematic. The lack of system and the unpredictability of it, I think this is

really interesting.

!

Jan: I would describe you as a professor who tries to prove to the world that he

doesn’t have to know (what) that he is doing. (Laughter) del Suggest keep ‘what’

and keep (laughter) or [laughing]

!

James: I like that. For if were going to talk about art then none of us are going to be

in control much of the time. If you were to succeed miraculously in clearing all this up

I think it would be much less interesting.

!

Seeing without Objects: Visual Indeterminacy and Art

(PDF Available) in Leonardo 39(5):394-400 · October 2006 with 679 Reads

definition of what is valuable from margaret boden

The problem, rather, is

in getting the computer to generate and prune

these combinations in such a way that most, or

even many, of them are interesting—that is, valuable.

Computer Models of Creativity Margaret Boden

Boden suggests 3 different types of creativity:

combinatorial exploratory and transformative

may be a useful way to think about value in art

“Creativity can be defined as the ability to generate

novel, and valuable, ideas. Valuable, here, has

many meanings: interesting, useful, beautiful, simple,

richly complex, and so on. Ideas covers many

meanings too: not only ideas as such (concepts,

theories, interpretations, stories), but also artifacts

such as graphic images, sculptures, houses, and jet

engines. Computer models have been designed to

generate ideas in all these areas and more (Boden……………….

As for novel, that has two importantly different

meanings: psychological and historical. A psychological

novelty, or P-creative idea, is one that’s new

to the person who generated it. It doesn’t matter how

many times, if any, other people have had that

idea before. A historical novelty, or H-creative idea,

is one that is P-creative and has never occurred in

history before

Combinational creativity produces unfamiliar

combinations of familiar ideas, and it works by

making associations between ideas that were previously

only indirectly linked. Examples include

many cases of poetic imagery, collage in visual art,

and mimicry of cuckoo song in a classical symphony.

Analogy is a form of combinational creativity

that exploits shared conceptual structure

and is widely used in science as well as art. (Think

of William Harvey’s description of the heart as a

pump, or of the Bohr-Rutherford solar system

model of the atom.)

It is combinational creativity that is usually

mentioned in definitions of “creativity” and that

(almost always) is studied by experimental psychologists

specializing in creativity. But the other

two types are important too

Exploratory creativity rests on some culturally

accepted style of thinking, or “conceptual space.”

This may be a theory of chemical molecules, a style

of painting or music, or a particular national cuisine.

The space is defined (and constrained) by a

set of generative rules. Usually, these rules are

largely, or even wholly, implicit. Every structure

produced by following them will fit the style concerned,

just as any word string generated by English

syntax will be a gramatically acceptable English

sentence.

(Style-defining rules should not be confused

with the associative rules that underlie combinational

creativity. It’s true that associative rules generate—

that is, produce—combinations. But they

do this in a very different way from grammarlike

rules. It is the latter type that are normally called

“generative rules” by AI scientists.)

In exploratory creativity, the person moves

through the space, exploring it to find out what’s

there (including previously unvisited locations)—

and, in the most interesting cases, to discover both

the potential and the limits of the space in question.

These are the “most interesting” cases

because they may lead on to the third form of creativity,

which can be the most surprising of all.

In transformational creativity, the space or style

itself is transformed by altering (or dropping) one

or more of its defining dimensions. As a result,

ideas can now be generated that simply could not

have been generated before the change. For

instance, if all organic molecules are basically

strings of carbon atoms, then benzene can’t be a

ring structure. In suggesting that this is indeed

what benzene is, the chemist Friedrich von Kekule

had to transform the constraint string (open curve)

into that of ring (closed curve). This stylistic transformation

made way for the entire space of aromatic

chemistry, which chemists would explore

[sic] for many years.

The more stylistically fundamental the altered

constraint, the more surprising—even shocking—

the new ideas will be. It may take many years for

people to grow accustomed to the new space and

to become adept at producing or recognizing the

ideas that it makes possible. The history of science,

and of art too, offers many sad examples of people

ignored, even despised, in their lifetimes whose

ideas were later recognized as hugely valuable.

(Think of Ignaz Semmelweiss and Vincent van

Gogh, for instance. The one was reviled for saying

that puerperal fever could be prevented if doctors

washed their hands, and went mad as a result; the

other sold only one painting in his lifetime.)

Transformational creativity is the “sexiest” of

the three types, because it can give rise to ideas

that are not only new but fundamentally different

from any that went before. As such, they are often

highly counterintuitive. (It’s sometimes said that

https://www.comedianscomedian.com/328-seann-walsh/

Listening to sean walsh

he describes being on stage and hearing a huge number of people laughing and then reading reviews which were negative

this shows

a he is looking for approval outside himself to validate what he does

he is n to sure how to evaluate what he does

he is aware that it is important for his work to have some value

he is not sure about any of this

i have not listened to the full interview!!

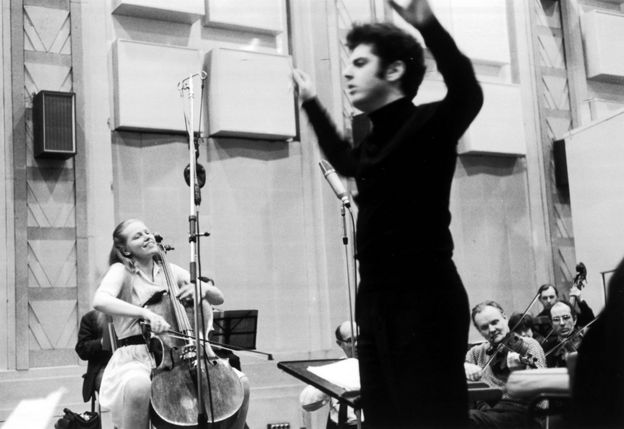

The Cellist: Will Gompertz reviews the Royal Ballet work inspired by Jacqueline du Pré ★★★★☆

It might sound a bit rich coming from someone not noted for his good looks, but beauty isn’t getting the respect it deserves.

Not so long ago it was all the rage.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant was pro-beauty. He considered it a form of morality.

Einstein said it enticed the inner child out of us.

And wise old Confucius believed everything has beauty, but not everyone sees it.

Bringing it into plain sight used to be the job of artists, authors and composers wearing billowing white shirts with splendid frou-frou collars last seen on Duran Duran in the 1980s. But pop’s New Romantics were no match for the relentless march of modernism with its frigid less-is-more dogma and strict no-frills dress code.

I blame Marcel Duchamp.

He was the artist who proposed a urinal as a work of art back in 1917. He chose it precisely because it was, as he said, anti-retinal: an unattractive sight. It was intended as an act of destruction: an enamelled Exocet missile aimed at the heart of a bourgeois art establishment aligned to a political class responsible for a horrific, bloody war.

Image copyrightALAMY

Image copyrightALAMYIt was no time for beauty, Duchamp argued.

If art meant anything at all it should speak the truth about what was happening, which was ugly and base. His toilet scored a direct hit, romanticism was dead. Henceforth, beauty was naff and frivolous; cynicism was the new religion for our secular age. Music became dissonant, literature became fragmented, theatre became absurd, and art turned ugly.

Caught up among the collateral damage was classical narrative ballet, the most romantic of art forms.

Tutus and fairies had no place in the new order. Ballet was dispatched to the art dog house, to be consumed by the people of Tunbridge Wells, or somewhere equally as uncool, where locals dress in brown tweed and mustard corduroy and consider Country Life a magazine not a brand of butter.

And that is where ballet remains, with some of the most beautiful choreography and music ever created written off as elitist and irrelevant.

It’s a shame.

To see exceptionally talented dancers express emotions and story through graceful movement accompanied by a full orchestra is a sensuous experience like no other.

It isn’t posh or difficult or any more expensive than going to a gig or a Premier League football match.

It isn’t stuck in the past either.

The Cellist has just opened at the Royal Opera House in London. It is a new ballet by Cathy Marston telling the true story of Jacqueline du Pré, the prodigiously gifted post-war cellist whose career and life were cruelly cut short by multiple sclerosis.

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSE

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSEThe tragic-romantic tale of love and loss centred around a young woman is classic classical ballet.

The difference here, though, is the subject of our heroine’s affections isn’t her lover and husband, the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim, but her instrument: the eponymous cello.

Barenboim gets to play the gooseberry, as he watches his wife enthusiastically pluck her instrument, brought vividly to life by the Royal Ballet’s newly promoted principal dancer, Marcelino Sambé.

Lauren Cuthbertson takes the role of Jacqueline du Pré, and, as you would expect from one of the finest dancers of her generation, gives a wonderfully nuanced and intelligent performance.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightREX

Image copyrightREX The show begins with us meeting a very young Jacqueline (played by a student at White Lodge ballet school) at home with her parents where she is having her first encounter with the instrument that would make her an international superstar by the mid-60s.

Enter Cuthbertson, who stands behind Sambé (her cello) and mimes playing him to the sound of Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

It is… beautiful.

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSE

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSE

He then lifts her and pirouettes as she maintains a seated playing position, which I must admit, is less beautiful and took my mind back to Duchamp and lavatories. No matter, it is one of very few awkward moments in a piece full of newly found positions, which races through Du Pré’s life in 60 minutes.

Barenboim enters the fray, leading to a memorable pas de trois, before dread looms in the form of an inexplicable shake in the cellist’s right leg. The transformation from a woman at the very top of her game to one confronting an unknown terror is undertaken with enormous skill and sensitivity by Cuthbertson, whose on-stage chemistry with Sambé transmits her love for him – her cello – with an intensity that makes the hopelessness of her situation profoundly moving.

To have a talent such as hers is a blessing, to have it snatched away so soon by a silent, malevolent condition seems so cruel, to her and us. It is the tragedy of something truly marvellous being destroyed.

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSE

Image copyrightROYAL OPERA HOUSE

That is not a romantic condition, it was a fact of life for Jacqueline du Pré, a reminder that beauty should be cherished not banished. It is not uncool or naff, it is an ideal worth believing in and striving for and appreciating.

That is the message of The Cellist, delivered with aplomb by the dancers and orchestra who accompany them with a score referencing pieces by Elgar, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Rachmaninoff and Schubert.

Beautiful.

Note: The Cellist can be seen on screen in a live link to selected cinemas on 25 February.

Patriciaoxley@hotmail.com

This blog is a notebook for me to record statements around the issues:

is it art?

what is art?

if it is art, is it good art?

What is good art?

Why do people do things that we/they call art

Because it is my own blog and notebook, I reserve the right to be incoherent and disorganized. Having said that, I welcome comments that further the enquiry from people who can tolerate this.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-49892553

Patriciaoxley@hotmail.com

Aeon.co

man saying that if he shows a picture of a cat for 30 seconds several times and then shows a picture of a different car for 30 seconds it will seem that the new cat is seen for longer than 30 seconds.

when the brain sees something that is novel it has to burn more energy to represent it

novelty in art?n@@ili

Quickdraw with google

Over 15 million players have contributed millions of drawings playing Quick, Draw!These doodles are a unique data set that can help developers train new neural networks, help researchers see patterns in how people around the world draw, and help artists create things we haven’t begun to think of. That’s why we’re open-sourcing them, for anyone to play with.