drawings, and other materials. But it’s also an exploration in building smart tools and interfaces that allow artists and musicians to extend (not replace!) their processes using these models. Magenta was started by some researchers and engineers from the Google Brain team, but many others have contribute

But art… art is sacred. Art is an expression of human sentiment and emotion. Computers stand zero chance of consigning human creativity to the history books. Right? Well, maybe. We’re already seeing the early signs that art will be disrupted by machine intelligence and automation.

Joe rogan neil de grasse Tyson6 sept 19

Called rolling hills but noquote from neil at beginning:

re Van Gogh starry night

’you Know what I like about starry night? It’s not what Van Gogh saw that night. It’s what he felt.’

The above said in measured momentous tones with knowing emphasis on felt.

JR bless him does [not let this pass ‘how do you know what he felt?

neil seems a little perturbed by the question his answer is:

’because this is not a representation of reality And anything that deviates from reality is reality filtered through your senses and I think art at its highest is exactly that. If this was an exact depiction of reality it would be a photograph and I don’t need the artist.’

JR ‘oh okay’

neil: ‘so, è ven photographs that take you to a slightly other dimension as you gaze upon them it’s more than what was actually going on at the time and that’s art taken to the craft of photography,

JR ‘and that’s why you like it?’

neil

That’s one of the reasons why. I think it was the very first painting where its title is the background. Think about that This could have been called oh you know obviously in the full painting, this is a snippet

JR

A TOWN

NEILL

YEAH THERE’s A TOWN THERE THERE’s A CYPRESS TREE there is a church steeple. It could have been called cypress tree. It could have been called sleepy village it could have been

calld rollin hills

bur no it’s called starry night and everything in front of it everything in front of it is just in the way. How often do you paint something where the title is the background. That’s my point and in this particular case the background is the universe and so for me this was a pivot point in art and this was 1889 which is recent given the history of paintings that go all the way back. So yeah

JR Is that your favourite painting ever

neil. I have to say yes

https://www.ibm.com/blogs/think/2019/03/ai-is-not-magic/

Anything that can be easily described, can be programmed.

but I WANT TO USE IT for finding things i can’t describe

Brains on Art, Why the Art Encounter may not be such a Special Experience

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY ARTICLE Front. Hum. Neurosci., 09 June 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00295 Artworks as dichotomous objects: implications for the scientific study of aesthetic experience

Representational artworks are dichotomous in that they present us with two distinct aspects at once. In one aspect we are aware of what is represented while in the other we are aware of the material from which the representation is composed. The dichotomy arises due the incompatibility, indeed contradiction, between these aspects of awareness, both of which must be present if we are to fully appreciate the artwork.

I hypothesize that the degree of manifest dichotomy in a work determines the strength of its aesthetic effect, and propose this could be experimentally tested. I conclude that scientific studies of aesthetic experience should take the dichotomous nature of artworks into account.

Seen at closer quarters the engine hovers between appearing as solid metal and buttery paint and the poor passengers in the open-top carriages almost dissolve into gray blobs. If we focus too closely on a single patch of paint the object it forms disappears and with it the dichotomous effect.

The dichotomy between these two aspects of awareness is one that all representational works of art exploit because they appear both as an arrangement of materials such paint, ink, plaster, metal, stone, etc. and as whatever they represent. As we will see, many theorists have argued is a requirement of appreciating such artworks that we are aware of both distinct appearances simultaneously.

But I will argue there is something special about the way artists exploit this property that is an important part of how artworks function aesthetically and which any scientific explanation of aesthetic experience will need to take into account.

In particular, there is a recurring suggestion that pictures and paintings induce a kind of “dual” or “split” state of mind in which we are aware of distinct and incompatible aspects of the work simultaneously.9 Many authors characterize this state as “impossible,” “contradictory,” or “paradoxical,” in other words as irrational. Pat: willing suspension of disbelief

there are three aspects to the dichotomous nature of representational artworks that can condition our aesthetic response: first, we are aware of the discrepancy between the matter from which the artwork is composed and what it represents; second, we are aware of discrepancies between the way things are represented in the artwork and how we would expect them to look in reality; and third, we are aware of many distinct conflicting meanings that attach to the same work at the same time.

It is not pictures in themselves that are paradoxical, contradictory, or impossible but our perceptual and cognitive responses to them.

Developmental studies

perceptual psychology

works of art are generally formed through integration of two incompatible elements, one of these being an attempted communication and the other an artistic structure that contradicts the communication.” (p. 235) It is through our experience of this incompatibility that works of art, not just visual but also theatrical and literary, have their power to move us.

Julian Bell argues that what is significant about representations is that they confront us with a contradictory sense of things that are present but also absent (Bell, 1999). He talks about the “mark” as a material object to which we assign associations, whether this is the intentional mark made by artist or the incidental mark made the skid of a tyre, or a boot print in the ground:

We see it and we see past it, or into it; it is what it is and a reminder of something else besides. It is when we see something in that double, ambivalent manner that we call it a mark. Seen another way, it might be so many grams of paint, or of rubber, or of a hole of such and such a depth in the ground.15

Church’s explanation of this double consciousness draws on a Kantian framework in which “… we experience different ways of seeing, or different appearances, as both conflicting and convergent whenever we are conscious of objects…” (p. 109). In her view, an object—the painting—can also have the appearance of something else—a landscape—because it is a requirement of conscious seeing in general that we conceive the different aspects from which it is possible to view a scene, but that these converge in our own single view. Our perception of the painting as an object conflicts with but also converges with its appearance as a landscape. In this way, Church retains the contradictory dualistic character of representations while seeking overall conceptual unity in the experience.17

we can see how these dichotomous properties have been exploited or manipulated by artists in order to condition our responses to their work.

of Guiseppe Arcimboldo’s arrangements of fruit, vegetables, flowers, and other objects that metamorphose into formally posed heads:

The overall effect is to induce a degree of perceptual dissonance that is exciting, if not somewhat disturbing.

But like all true paradoxes, The Treason of Images cheerfully resists any attempt at rationalization and stubbornly asserts the fact that the shape above the words is clearly a pipe, and yet—being confected from paint—is also not a pipe.

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1928/29, Oil on canvas, 62 × 81 cm, Los Angeles, County Museum. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015.

Robert Gober, Untitled, 1990, Beeswax, pigment, and human hair, 60 × 44 × 29 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photograph by the author. © Robert Gober, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

Rachel Whiteread, Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial, 2000, Concrete, Judenplatz, Vienna. Image source: Wikimedia Creative Commons

3 kinds of dichotomy:

- the disparity between its material constitution and the objects it represents.

- the disparity between how we expect an object to look and how it actually looks in the work.

- The third way in which artworks manifest their dichotomous nature lies in their capacity to elicit a multitude of distinct and contradictory meanings in the mind of the viewer.

It is characteristic of great works of art that they cannot be narrowly or precisely defined. Some researchers have argued certain works of art are great precisely because they evoke multiple or incomplete meanings (Zeki, 2004

The neurology of ambiguity

Semir Zeki*

University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK

Received 14 April 2003

The way artworks exploit these three kinds of dichotomy may be one of the factors distinguishing them from representational objects in general. For while all pictures and representational objects engender multiple and contradictory states of perception by their dichotomous nature, works of art do this to a greater extent.

Or consider Figure Figure1111 showing a modern train crossing the same railway bridge depicted by Turner in Figure Figure2.2. Although pleasant enough, it has none of the difficulty, expressiveness, or atmosphere elicited by Turner’s painting of the same subject. We have little reason to pay attention to the fabric from which it is composed, nor does it surprise us as a depiction of how a train would look crossing a bridge.

For many people, of course, the Jansch sculpture will be aesthetically preferable to the Picasso precisely because the arrangement of matter follows more closely the expected form of a horse. In this sense it is more “realistic” or recognizable, and appears to show greater evidence of skill in its construction. It is probable that the level of expertise of the viewer will be an important factor in this judgment, with art experts being inclined to favor the Picasso because it places greater demands on imaginative resources and because it has deeper poetic resonance (the leather of the seat evokes the skin of the animal, we think of holding the handle bars and “taking the bull by the horns,” of Picasso conjuring up a potent symbol of Spanish vitality from the among the privations of wartime Paris, etc.). For all its skilful construction, the wooden horse fails to ignite as many diverse associations, and therefore ranks as a lesser work of art.

based on all of the above:

Based on these observations I offer the following hypothesis: that our aesthetic experience of artworks is determined, in part, by our awareness of their dichotomous properties. This hypothesis predicts a correlation between manifest degree of dichotomy and aesthetic effect, such that objects manifesting greater degrees of perceived dichotomy will elicit a correspondingly stronger aesthetic experience.23 The hypothesis further predicts higher levels of art expertise will be a factor in preference for greater degrees of perceived dichotomy.

there are many discussions of ambiguity in the literature (Empson)

different kinds of ambiguity:

empson

Kaplan A. I., Kris E. (1948). Esthetic ambiguity. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 8, 415–435. 10.2307/2103211

“disjunctive ambiguities” containing several alternative and mutually exclusive meanings, and “integrative ambiguities” where manifold meanings interact to form a complex and shifting pattern of overall sense. These different kinds of ambiguity are employed in literary works to enhance their aesthetic value.

Berlyne (1971) discussed the way cubist paintings can present the viewer with contradictory cues, where one segment of the painting can belong at the same time to two objects. These cues can be registered simultaneously, in which case they generate incongruity or conflict, or they can suddenly alternate in meaning, with one interpretation replacing another, giving rise to an increase in arousal or surprise. Berlyne D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and Psychobiology. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar

Jakesch and Leder (2009) showed that moderate levels of perceived ambiguity or dissonance in modernist works of art are preferred to those with low levels.

Finding meaning in art: Preferred levels of ambiguity in art appreciation

In order to leave the last word to an artist I close with a brief extract from a conversation between the painter Francis Bacon and the art critic David Sylvester:

Bacon: I want a very ordered image, but I want it to have come about by chance.

Sylvester: It’s a matter of reconciling opposites I suppose, of making the thing be contradictory things at once.

Bacon: Well, isn’t it that one wants a thing to be as factual as possible and at the same time as deeply suggestive, or deeply unlocking of areas of sensation…? Isn’t that what all art is about?26

http://va.lv/en/research/research/leveraging-ict-product-innovations-enhancing-codes-modern-art

Leveraging ICT Product Innovations by Enhancing Codes of Modern Art

Updated 18.09.2018.

The aim of this project is to raise the interest of a wide ranging public for contemporary art and to point out the newest creative tendencies in the collective thinking of art. On a larger scale, the project tends to describe the language of art in the nearest future and thus to foresee the monetary value of the art of tomorrow. The task is to create an innovative digital game in the cross-cutting genres of arthouse, educational and serious game.

As interactive media, digital games have a great potential to integrate people into fields that would otherwise not meet their interest. The game would develop the creative skills of players and teach them the current trends in digital art. The game would also collect the results of players forming a database of artistic means that will lead to scientific conclusions about future art. In the meantime, the game would project the inheritance of art from the age of modernism into the digital world by teaching the player to recognize it (for instance, pixel aesthetics is a successor to cubism and constructivism).

The paper presents an overview of digital art games and the historical background of their aesthetics. The Design Science Research method will be used in this project in order to cross-cut such remote fields as the general public and the arthouse world, codes of modern art and the taste of the general public. Taking into account that art today is largely interactive, the new game will let its user play around with trends of modern art such as vaporwave, glitch and others, and to create new ones. Thus, the project deals with the problem of knowledge cache and cultural segregation that characterizes modern art: being specific to a great extent, it is difficult to access a large segment of the public.

The scientific objective of the project is research in the field of ICT and modern art in Latvia in order to find new ideas to benefit ICT rooted in the contemporary cultural tradition that has already lasted over one hundred years and which embodies the basic intellectual codes of today.

The aim of this project is to form a new methodology of ICT products’ creation using knowledge of the theory of modern art (hereinafter – TMA) and its subsequent postmodernity expression, paving the way for a novel approach to culturally based digital production. The planned action is to experimentally create models, prototypes and examples of ICT as bearers of intellectual capital and analyze existing products while forming this kind of methodology. The impact of the new ICT methodology is a transfer of knowledge about contemporary artworks into ICT.

Thus, it is an impact on the Latvian digital society as knowledge about modern art that is insufficient at present. The major deliverable of this project will be a new methodology for the translation of art codes into ICT products, taking into account that the ICT and TMA are specifically segregated / unconnected fields and today’s interdisciplinary scientific approach demands their crosscutting.

Key words: knowledge society, knowledge value chain, modernism, hidden culture codes, ICT product development, intellectual capital, creative industries.

PostDoctorate Research Project

Supported by ERDF

Project manager: assistant professor Ieva Gintere

Scientific consultants: dr.phys. Atis Kapenieks, dr.phil. Martin Boiko

Project duration: 01.09.2017. – 31.08.2021.

Project number: 1.1.1.2/VIAA/1/16/106

Partner: Interactive Agency Cube

In a collaboration with artist Kristaps Biters

Accomplished activities of the project:

- Activity No.1. State-of-the art in the field of modernism codes and its intersection with ICT

- Activity No.2. In-depth interviews and their analysis (interviews of artists, digital art representatives and ICT specialists, analysis of interviews, description of art codes) (scientific seminar)

- Activity No.3. Delphi method, digital art expert interviews

- Activity No.6. Conference paper. Gintere, I., Zagorskis, V., Kapenieks, A. (2018). “Concepts of E-learning Accessibility Improvement – Codes of New Media Art and User Behaviour Study”. 10th CSEDU International Conference on Computer Supported Education, proceedings, Portugal, Madeira, March 15-17

- Popular-science review

- Activity No.8. Concept of product prototype

- Activity No.9. Scientific publication. Gintere, I., Zagorskis, V., Kapenieks, A. (2018). “Concepts of E-learning Accessibility Improvement – Codes of New Media Art and User Behaviour Study”. 10th CSEDU International Conference on Computer Supported Education, proceedings, Portugal, Madeira, March 15-17 , vol. 1, p. 426-431.

- Activity No.9. Design of product prototype. Innovative digital game

- Activity No.10. Ethics of the project

- Activity No.12. Renewal of the study path

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-48043765

In 2015, Tillemann-Dick was confronted with another health problem.

She was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive skin cancer, thought to be a result of the anti-rejection drugs she had taken for her lungs.

Treatment required chemotherapy, radiation and surgery, including a particular procedure that required cutting a nerve on her face, affecting muscle movement on the right side of her mouth, the Washington Post reported.

“Life is full of death. Music, full of sorrow”, Tillemann-Dick wrote in her 2017 book, The Encore: A Memoir in Three Acts.

“Great artists have always amplified both.”

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-47827346

hy do we like magic when we know it’s a trick?

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESWhy do we enjoy looking at magic?

Everyone knows these are tricks and not “real”. It’s not as though we don’t know our senses are being deceived. But we still watch and wait for the reveal.

It might be more of a surprise to find there is a university laboratory dedicated to understanding magic – the Magic Lab, part of the psychology department at Goldsmiths, University of London.

It’s part of a growing interest in putting magic under much more rigorous, scientific scrutiny.

Gustav Kuhn, reader in psychology at the university, is head of the Magic Lab – which stands for Mind Attention and General Illusory Cognition.

‘Misdirection’

As the title suggests, the principles behind magic are rooted in areas that overlap with psychology – perception, attention and how we process information.

Magic is about manipulating our perceptions, “exploiting cognitive loopholes,” says Dr Kuhn – and understanding how magic works is being recognised as having wider implications.

“Misdirection” is a key part of magic – getting people to not look at what’s important, but to distract them, change the subject, use a dramatic prop and push their attention elsewhere, so they do not see what is happening in front of their eyes.

It’s being used to to examine areas such as road safety, says Dr Kuhn, looking at how to make sure drivers can really focus on what’s important.

“How do people fail to see something even though they are looking at it?” he says.

Fake news

It’s also applicable to bigger social and political questions, he says, such as how to respond to “fake news” and false information on social media.

The lesson of magic, says Dr Kuhn, is that even if something is recognised as false, it still makes an impression and steals our attention, and researchers are looking at how understanding magic can help to investigate the world of conspiracy theories and fake information.

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPAAnother key part of a magic trick is the “forcing technique”.

This is where someone thinks they are choosing a card at random, but the magician is really manipulating their decision and the “choices” are false.

“Free will is an illusion. People are much more suggestible than they think. All of our perceptions are very malleable,” says Dr Kuhn.

This suggestibility and use of false options can be misused in a political sense, he says.

But it’s also important in understanding how eye-witness evidence can be so “highly subjective”, with implications for the legal system.

‘Nature of perception’

The attitude towards examining the connections between magic and science has gone from scepticism to becoming one of the hottest research topics, says Dr Kuhn.

This week the Wellcome Collection in London is launching an exhibition into the Psychology of Magic, looking at what conjuring can tell us about the human mind and the “nature of perception”.

The University of London is also running an exhibition “Staging Magic – The Story Behind The Illusion”.

Dr Kuhn says he was interested in magic before he became interested in studying psychology.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES“I loved watching magic, the clever puzzles and techniques, trying to understand how it worked,” he says.

When he learned how to perform magic, he says he enjoyed the sociability, with the tricks becoming ice-breakers for the awkward years of growing up.

Great art

Great magicians can perform tricks in a way that moves people like great art, he says.

He mentions watching a card trick from the Spanish magician, Juan Tamariz.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES“I still don’t know he did it, it was so beautiful. It almost connects you to childhood, when the world seems very magical.”

Watching him show a card trick was like seeing “Jimi Hendrix performing a guitar solo”.

He says that performing magic seems to have a particular appeal to people who are otherwise shy or introverted.

Image copyrightWELLCOME

Image copyrightWELLCOMEIn the psychology department, all the students can take an option in magic, and Dr Kuhn says learning to perform tricks has proved a big help with confidence.

“It really boosts self-esteem,” he says.

Hannah Laurence, a first-year student on the course, said that learning a range of tricks helped her to meet other students and to “step outside of my comfort zone”.

Making sense

But what’s the appeal of magic?

Dr Kuhn says part of the fascination is trying to reconcile something that we’ve seen, with what we know is not really possible.

Rabbits don’t suddenly appear in top hats from nowhere. People can’t get sawn in half and walk away.

He says it’s a sensation that produces a deep-rooted response, trying to reconcile this “cognitive conflict” and triggering part of the brain, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

From a very early age we are drawn to what we don’t understand, says Dr Kuhn, with an evolutionary incentive to try to make sense of what seems to be unexplained.

“We learn to develop this way,” he says.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESDr Kuhn likens the appeal of a magic trick to that of a horror film.

If such bloodshed was seen in real life, he says, it would be traumatic and awful, but when it’s shown in the safety of a movie, the fear becomes something that people can enjoy.

Likewise, if we were confronted with something which disorientated and distorted our senses, it would be deeply disturbing, but when it’s put into the context of a magic trick, it becomes entertaining and amusing.

The fact that we know it’s not real is an essential part of making it an enjoyable sensation.

“It’s an exciting time to be researching magic,” says Dr Kuhn, showing how trickery can give “fresh insight into the strengths and weaknesses of our own minds”.

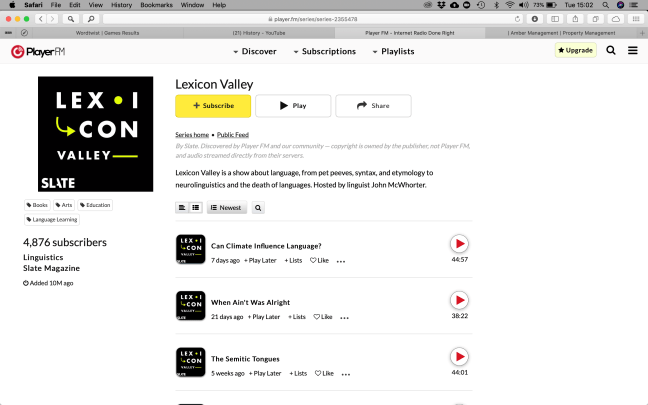

https://player.fm/series/series-2355478

podcast on here refers to people who get very mad when others use a language item they cont agree with

maybe this is related to the heat that is in evaluations of art and maybe the conflation of socail approval of yourself and approval of your art

approval of yourself and approval of your art