Why Fractals Are So Soothing

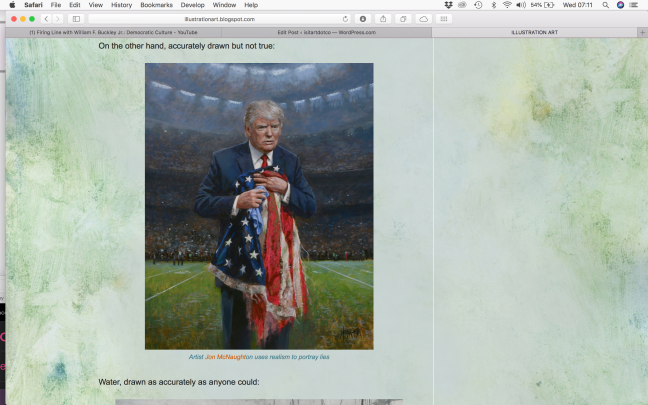

Jackson Pollock’s paintings mirror nature’s patterns, like branching trees, snowflakes, waves—and the structure of the human eye.

Morteza Nikoubazl / Reuters

FLORENCE WILLIAMS JAN 26, 2017 SCIENCE

Share Tweet …

TEXT SIZE

Like The Atlantic? Subscribe to The Atlantic Daily, our free weekday email newsletter.

When Richard Taylor was 10 years old in the early 1970s in England, he chanced upon a catalogue of Jackson Pollock paintings. He was mesmerized, or perhaps a better word is Pollockized. Franz Mesmer, the crackpot 18th-century physician, posited the existence of animal magnetism between inanimate and animate objects. Pollock’s abstractions also seemed to elicit a certain mental state in the viewer. Now a physicist at the University of Oregon, Taylor thinks he has figured out what was so special about those Pollocks, and the answer has deep implications for human happiness.

MORE FROM OUR PARTNERS

Aeon

Why We Can Stop Worrying and Love the Particle Accelerator

Kids Aren’t Interested in Moral Conflict

How We Evolved From Drunken Monkeys to Boozy Humans

This question didn’t always occupy his professional time. Taylor’s day job involves finding the most efficient ways to move electricity: in multiple tributaries like those found in river systems, or in lung bronchi or cortical neurons. When currents move through things such as televisions, the march of electrons is orderly. But in newer, tiny devices that might be only 100 times larger than an atom, the order of currents breaks down. It is more like ordered chaos. The patterns of the currents, like the branches in lungs and neurons, are fractal, which means they repeat at different scales. Now Taylor is using ‘bioinspiration’ to design a better solar panel. If nature’s solar panels—trees and plants—are branched, why not manufactured panels?

Taylor describes himself as a type of thinker who jumps across disciplines to solve problems. In addition to his credentials as a physicist, he is a painter and photographer with an advanced art degree. He’s known as a bit of an eccentric around campus. He frequently paddles across Waldo Lake in Oregon when he’s searching for insights, and his hair is so famous it’s almost a distraction. Long and curly, it resembles the distinctive locks of Sir Isaac Newton in his prime. The public affairs office of the university once actually Photoshopped it out of a publication.

Through his meandering career trajectory, Taylor never lost his interest—obsession, really—in Pollock. While at the Manchester School of Art, he built a rickety pendulum that splattered paint when the wind blew because he wanted to see how ‘nature’ painted and if it ended up looking like a Pollock (it did.) Then some years ago, he had a seminal insight while working on nanoelectronics. “The more I looked at fractal patterns, the more I was reminded of Pollock’s poured paintings,” he recounted in an essay. “And when I looked at his paintings, I noticed that the paint splatters seemed to spread across his canvases like the flow of electricity through our devices.”

Using instruments designed to measure electrical currents, Taylor examined a series of Pollocks from the 1950s and found that the paintings were indeed fractal. It was a little like discovering that your favorite aunt speaks a secret, ancient language. “Pollock painted nature’s fractals 25 years ahead of their scientific discovery!” He published the finding in the journal Nature in 1999, creating a stir in the worlds of both art and physics.

Benoit Mandelbrot first coined the term ‘fractal’ in 1975, discovering that simple mathematic rules apply to a vast array of things that looked visually complex or chaotic. As he proved, fractal patterns were often found in nature’s roughness—in clouds, coastlines, plant leaves, ocean waves, the rise and fall of the Nile River, and in the clustering of galaxies. To understand fractal patterns at different scales, picture a trunk of a tree and a branch: they might contain the same angles as that same branch and a smaller branch, as well as the converging veins of the leaf on that branch. And so on. You can have fractals creating what looks like chaos.

Taylor was curious to know if the fractals in the Pollocks might explain why people were so drawn to them, as well as to things such as pulsating screensavers and stoner light shows at the planetarium. Could great works of art really be reduced to some nonlinear equations? Only a physicist would ask. So Taylor ran experiments to gauge people’s physiological response to viewing images with similar fractal geometries. He measured people’s skin conductance (a measure of nervous system activity) and found that they recovered from stress 60 percent better when viewing computer images with a mathematical fractal dimension (called D) of between 1.3 and 1.5. D measures the ratio of the large, coarse patterns (the coastline seen from a plane, the main trunk of a tree, Pollock’s big-sweep splatters) to the fine ones (dunes, rocks, branches, leaves, Pollock’s micro-flick splatters). Fractal dimension is typically notated as a number between 1 and 2; the more complex the image, the higher the D.

“We’ve analyzed the Pollock patterns with computers and compared them to forests, and they are exactly the same.”

Next, Taylor and Caroline Hägerhäll, a Swedish environmental psychologist with a specialty in human aesthetic perception, converted a series of nature photos into a simplistic representation of the landforms’ fractal silhouettes against the sky. They found that people overwhelmingly preferred images with a low to mid-range D (between 1.3 and 1.5.) To find out if that dimension induced a particular mental state, they used EEG to measure people’s brain waves while viewing geometric fractal images. They discovered that in that same dimensional magic zone, the subjects’ frontal lobes easily produced the feel-good alpha brainwaves of a wakefully relaxed state. This occurred even when people looked at the images for only one minute.

EEG measures waves, or electrical frequency, but it doesn’t precisely map the active real estate in the brain. For that, Taylor has now turned to functional MRI, which shows the parts of the brain working hardest by imaging the blood flow. Preliminary results show that mid-range fractals activate some brain regions that you might expect, such as the ventrolateral cortex (involved with high-level visual processing) and the dorsolateral cortex, which codes spatial long-term memory. But these fractals also engage the parahippocampus, which is involved with regulating emotions and is also highly active while listening to music. To Taylor, this is a cool finding. “We were delighted to find [mid-range fractals] are similar to music,” he said. In other words, looking at an ocean might have a similar effect on us emotionally as listening to Brahms.

Taylor believes that our brains recognize that kinship to the natural world—Pollock’s favored dimension is similar to trees, snowflakes and mineral veins. “We’ve analyzed the Pollock patterns with computers and compared them to forests, and they are exactly the same,” said Taylor. This dimension does more than lull us; it can engage us, awe us and make us self-reflect.

But why is the mid-range of D (remember, that’s the ratio of large to small patterns) so magical and so highly preferred among most people? Taylor and Hägerhäll have an interesting theory, and it doesn’t necessarily have to do with a romantic yearning for Arcadia. In addition to lungs, capillaries and neurons, another human system is branched into fractals: the visual system as expressed by the movement of the eye’s retina. When Taylor used an eye-tracking machine to measure precisely where people’s pupils were focusing on projected images (of Pollock paintings, for example, but also other things), he saw that the pupils used a search pattern that was itself fractal. The eyes first scanned the big elements in the scene and then made micro passes in smaller versions of the big scans, and it does this in a mid-range D. Interestingly, if you draw a line over the tracks that animals make to forage for food, for example albatrosses surveying the ocean, you also see this fractal pattern of search trajectories. It’s simply an efficient search strategy, said Taylor.

“Your visual system is in some way hardwired to understand fractals,” said Taylor. “The stress-reduction is triggered by a physiological resonance that occurs when the fractal structure of the eye matches that of the fractal image being viewed.” If a scene is too complicated, like a city intersection, we can’t easily take it all in, and that in turn leads to some discomfort, even if subconsciously. It makes sense that our visual cortex would feel most at home among the most common natural features we evolved alongside. So perhaps part of our comfort in nature derives from fluent visual processing.

If the cause of our relaxation is not entirely rooted in Thoreauvian romance, the solution surely is. We need these natural patterns to look at, and we’re not getting enough of them, said Taylor. As we increasingly surround ourselves with straight Euclidean built environments, we risk losing our connection to the natural stress-reducer that is visual fluency. It all adds up to yet another reason to bring greenery back to cities and get outside more often.

I had one final question for Taylor. I was interviewing him via Skype video because he was on holiday in Australia. His soft curls tumbled to the lower edges of the screen like a fine, galloping creek.

“Is your hair fractal?”

He roared with laughter. “I suspect my hair is fractal. The big question of course is whether it induces positive physiological changes in the observer!”